Toads of Spring

by Valerie (May 6, 2000)

revised August 5, 2003

We have two ponds in our gardens, one of which is at least 10 years old, and the other is brand new. The older one is a small, preformed heavy plastic liner sunk in the ground with a small pump to fuel a waterfall made of a pile of rocks. It is now quite overgrown with vegetation, both water plants and tree roots that have found their way over the lip of the pond and under the edge of the waterfall liner. These roots make a nice ladder for small creatures wanting to enter and leave the water and I've often seen toads crawling up the roots to get to the pile of rocks, where they can hide. We have two ponds in our gardens, one of which is at least 10 years old, and the other is brand new. The older one is a small, preformed heavy plastic liner sunk in the ground with a small pump to fuel a waterfall made of a pile of rocks. It is now quite overgrown with vegetation, both water plants and tree roots that have found their way over the lip of the pond and under the edge of the waterfall liner. These roots make a nice ladder for small creatures wanting to enter and leave the water and I've often seen toads crawling up the roots to get to the pile of rocks, where they can hide.

The new pond is larger (8'x6'x2½') with a cedar frame over a rim of landscaping logs. The liner is flexible rubber. At dusk, the males hop up on the rim and dive right in, like it is a swimming pool. This pond is a little harder for the toads to leave but they definitely seem to prefer its large size, perhaps because their voices echo a bit and sound louder, and we already have eggs in this one after only a couple of nights of toad serenades, triggered by some heavy rain we had several days ago.

The toads sing quite loudly and repeat a long trill over and over at regular intervals. When two or more males are singing at the same time, the pitch varies between the individuals but sometimes the songs alternate in perfect time and sometimes they overlap. The timing of each individual usually equals the others. If I disturb the serenading amphibians by viewing them with a flashlight, they will stop and freeze, sometimes in mid-trill. I'm not sure how they do it, but a male can just sit there for several minutes, with his throat all puffed out as if he is singing, but not move at all.

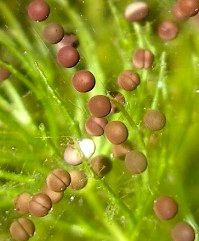

The males sometimes sing for several nights before attracting a female. When I find a male toad, if I hold him on his back he will sing softly, without inflating his throat sac. Turn him upright and he stops. This works all the time and I've never heard a reasonable explanation. After a male attracts a female, the singing stops and they get down to business, sometimes lingering on until morning. One unfortunate side to mating in water is that occasionally the female drowns, perhaps after getting tangled in the vegetation. Toads and frogs lay their eggs differently. Toads produce long strands of perfectly spaced eggs, which they string all around the plants, while frogs lay a large cluster in one place. Both types of eggs are surrounded by a clear gelatinous substance which protects them but is also water permeable so the eggs can receive oxygen.

|

Although the usual season for toad singing and egg laying is during late spring, sometimes the toads will become inspired later in the summer, seemingly independent of weather conditions. We've had toads singing as late as August and successfully laying eggs, so perhaps the arrival of new females can be a trigger.

Although the usual season for toad singing and egg laying is during late spring, sometimes the toads will become inspired later in the summer, seemingly independent of weather conditions. We've had toads singing as late as August and successfully laying eggs, so perhaps the arrival of new females can be a trigger.

The species in our area are Gulf Coast toads (Bufo valliceps). They are obviously very common as I've never seen any other amphibians in our yard. As soon as the eggs are laid, they start dividing (the first divisions are so large that they are visible to the naked eye) and take only about 24 hours to hatch; then the larvae cling to the gelatin that surrounded the eggs for the next 24 hours. They look like tiny embryos at this early stage and are simply absorbing the yolk that is in their extended stomachs, waiting while they grow a tail, form a mouth and gills sprout. These things happen by the following day and the next morning hundreds of the tadpoles are usually hanging on the surface tension of the water and the upper vegetation. By noon, they disperse a little lower in the water and start to swim around. This rapid development occurs in our area because of the temporary nature of most water sources. Few ponds and puddles last long enough for a leisurely development so the tadpoles are in a race against time to become independent of the water.

The species in our area are Gulf Coast toads (Bufo valliceps). They are obviously very common as I've never seen any other amphibians in our yard. As soon as the eggs are laid, they start dividing (the first divisions are so large that they are visible to the naked eye) and take only about 24 hours to hatch; then the larvae cling to the gelatin that surrounded the eggs for the next 24 hours. They look like tiny embryos at this early stage and are simply absorbing the yolk that is in their extended stomachs, waiting while they grow a tail, form a mouth and gills sprout. These things happen by the following day and the next morning hundreds of the tadpoles are usually hanging on the surface tension of the water and the upper vegetation. By noon, they disperse a little lower in the water and start to swim around. This rapid development occurs in our area because of the temporary nature of most water sources. Few ponds and puddles last long enough for a leisurely development so the tadpoles are in a race against time to become independent of the water.

If food is scarce, the omnivorous little creatures may eat each other. There have been times when the tadpoles begin to grow rapidly, but then slow considerably in their development and many disappear. When I look closely at the remaining individuals, they are almost flat because their stomachs are empty and they appear to be starving to death. I can only speculate that sometimes the algae is growing poorly and not all find enough to eat. Eventually the survivors really do look like tadpoles: tiny and black. They seem to spend a long period at this stage, then rather quickly absorb their tails and grow legs. The tiny toads are then about .25 to .3 of an inch long and completely black. They spend a lot of time clinging to the wooden edge of the pond, just above the water line, but gradually start to venture out into the yard to find food. They must find territories that are not occupied by the large adults, who would just as likely eat them as an insect of similar size. While thousands of tadpoles hatch, and dozens may make the transition to terrestrial life, our hot, dry summers ensure that mortality is quite high after they leave the relative safety of the pond and few survive to eventually breed.

If food is scarce, the omnivorous little creatures may eat each other. There have been times when the tadpoles begin to grow rapidly, but then slow considerably in their development and many disappear. When I look closely at the remaining individuals, they are almost flat because their stomachs are empty and they appear to be starving to death. I can only speculate that sometimes the algae is growing poorly and not all find enough to eat. Eventually the survivors really do look like tadpoles: tiny and black. They seem to spend a long period at this stage, then rather quickly absorb their tails and grow legs. The tiny toads are then about .25 to .3 of an inch long and completely black. They spend a lot of time clinging to the wooden edge of the pond, just above the water line, but gradually start to venture out into the yard to find food. They must find territories that are not occupied by the large adults, who would just as likely eat them as an insect of similar size. While thousands of tadpoles hatch, and dozens may make the transition to terrestrial life, our hot, dry summers ensure that mortality is quite high after they leave the relative safety of the pond and few survive to eventually breed.