|

The 14 pictures shown below were selected from about 140 photos I took during a five-day stay, in September, 2004, at or near Yellowstone National Park. I just used a reliable point-and-shoot 35mm film camera, the Fuji TW-300, purchased 15 years earlier. For folks wanting a closer look, a Gallery with larger versions of these images is available.

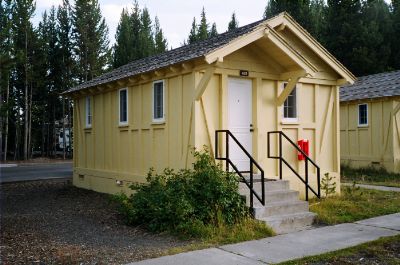

Despite their unassuming outer appearance, the cabins at Yellowstone's Lake Village, like this one (#523) where I stayed, were newly remodeled, cozy, attractive, and quite comfortable inside. In keeping with the quiet, simple, natural surroundings, they did not have phones, TVs, microwaves, fax machines, kitchens, or radios. They did have little coffee pots (with daily replenished one-pot filter bags of coffee grounds), thick quilts on the beds, writing desks, night tables, an efficient heater for the cool nights, and complementary bear-shaped bars of soap (a cute touch) for the sink and shower.

After settling into my cabin on the first day, I took a short walk. Rounding the corner of another small building, suddenly I found myself close to a herd of bison. They seemed to take no notice of me, but I'd been warned not to get closer than 25 yards. Too late. Staying otherwise quite still, I got out my camera and took a few pictures.

The next morning, I drove north and took advantage of several paths, pull-offs, or side roads to view and photograph Yellowstone River. This shot is of the 308 foot Lower Falls, taken from Artist Point. After the gigantic Yellowstone explosion of 640,000 years ago, a vast caldera, 30 miles across, 45 miles long, and thousands of feet deep was formed. Eventually this region filled with lava, including from the Canyon Rhyolite lava flow that covered what is now the Yellowstone canyon area, about 480,000 years ago. Hydrothermal activity weakened and softened much of that lava rock, and over many thousands of years river water could then erode it, channeling out the canyon. Both the Upper and Lower Falls were formed by the conjunction of such softer lava rock with the still quite hard, leading edge portions of the Canyon Rhyolite lava flow, in areas not yet affected by such hydrothermal activity at and upstream of the falls. Glaciers and their melt waters also helped form the current canyon shape.

Old Faithful is not now so frequent or powerful a symbol of Yellowstone as just a few decades ago. Subsequent earthquake activity has changed the system of steam channels and energy buildup below the famous geyser's cone so that now, instead of the 7000 gallons or more a minute eruptions of Yellowstone's past, geyser surges of 2000-3000 gallons a minute are more common. Still, even such lesser displays can be quite impressive. The average time between eruptions is now 94 minutes, but there was a variation of 5-10 minutes from this interval when I was there. Typical eruption heights are 106-184 feet.

The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is 20 miles long, 800-1200 feet deep, and 1500-4000 feet wide. Its present appearance largely dates from about 14,000 years ago, when the last ice age glaciers retreated.

Located along the Old Faithful area trail, the Lion geyser, pictured here, is one of a close set of four, called the Lion Group. The Lion's eruption is up to 80 feet and often preceded by a deep roaring sound. Hence the name. (I was rather lucky on 9/11 to see, in addition to Old Faithful, the eruptions of both the Lion and Beehive geysers. Neither of the latter two geysers has an interval predicted by the park staff. The Beehive, erupting to a height of 130-180 feet and often rivaling the intensity of Old Faithful, can be dormant for long periods.)

It is said of this Fishing Cone geyser, located on the shore of the West Thumb extension of Lake Yellowstone, that visitors to the park, back when fishing was allowed in the lake, used to catch a trout, swing the pole, dip the fish into its waters, and so cook their dinner. In fact, anglers used to sometimes be badly burned trying to get pictures of themselves straddling the geyser opening. (The water in the cone averages 199°F, the temperature required for boiling at the higher Yellowstone elevation.)

I was driving beside a small river and down a then empty stretch of road, on the northern portion of the park's Circle of Fire highway ring, when I caught sight of this bull elk grazing on the far bank of the stream. I parked, got out, crossed the road, enjoyed watching him for awhile, and took his picture. He appeared to notice me but not to be bothered. A few minutes later, as I was getting back into my car, it was suddenly like a typical paparazzi scene. At least a dozen other autos had stopped, briefly blocking the road, as people were frantic, dashing with big and little cameras, car doors left open, engines still running, children ignored, and politeness forgotten, in a mad, noisy crush to capture the moment.

Not quite the shape I would choose, but close, this natural hot tub looked very inviting on one blustery day. (There are stories of unfortunate visitors who, having thrown clothes and caution to the wind, jumped into such pots, only to be partially or fully boiled like lobsters. Plenty of signs now warn folks not to give in to temptation.)

Driving back toward my cabin, I saw in the distance a female elk coming toward me down the middle of the road, and managed to slow down, safely pull off, get my camera out of its case, and open the window just in time to get this shot as she walked on by.

An aerial view of the West Thumb Geyser Basin would reveal that there are several (7) hot springs or geysers almost exactly in a row, besides a number of other geysers, fumaroles, colorful deep pools, or thumb paint pots in that area. Active hydrothermal features also are present on the nearby Yellowstone Lake bottom. The high humidity and relatively warmer temperatures of this part of the park make it favorable for the growth of certain delicate plants, as well as comfortable as a resting spot for bison, elk, and other mammals. I took a picture of an elk calming lying in the steamy environs of one of the hot springs. Native Americans enjoyed camping in this part of Yellowstone. Crow Indians used to gather medicinal herbs near its hot waters.

A ranger at the Fishing Bridge Center Museum, after listening on his cell phone, told me and another visitor one afternoon that a couple grizzly bears had just been sighted eating wild raspberries at a spot several miles east of us, and told us how to reach the site. Well, the park road speeds do not accommodate the rate of travel our two cars would have been urged to achieve if at all permitted, and, upon our arrival, the bears were long gone. The family in the other vehicle stopped to watch a herd of bison. I had enjoyed several close encounters of the buffalo kind by then and so went up into the nearby hills for what I might find there. Alas, no further animal sightings were made, but I snapped a few photos where new growth was just starting under recently fire-blackened trunks. On my way back, this scene, of Lake Yellowstone's northern shore, seemed compelling. A front was moving in. That night we had the first snowfall of my stay.

One evening, just before nightfall, as I was walking again on the boardwalk that takes the visitor past dozens of geysers, hot springs, or fumaroles near the Old Faithful Lodge, I saw its namesake geyser erupt again and headed in that direction. Arriving almost too late in the day for photography, I managed to get this shot. It seemed a fitting final image for my stay inside Yellowstone Park. Just as the shutter clicked, a flock of Canada geese flew low overhead.

Their slopes bedecked with newly fallen snow, their peaks rising roughly 11,000-14,000 feet into the clouds, the Grand Tetons were my last view of the WY national park system before I headed home. An odyssey was ending.

|