by Larry

February, 2018What If There Were No People?In the span of time since life began on planet Earth, the duration of a species calling itself Homo Sapiens represents only about 0.006%. Yet we have reshaped the rest of the biosphere in ways far out of proportion to that miniscule temporal presence. Curious, as a thought experiment, I wondered then how things might be different if for some odd reason we were not around. That came close to being a reality, more than once, in fact. For example, around 70,000 years ago, a huge Toba Volcano eruption spewed so much ash, dust, and volcanic gases into the atmosphere that much sunlight was blocked from reaching the surface for years, and climate was radically altered long enough that many plants and animals died off. Average temperatures are thought to have plummeted 20 degrees. We would have been killed off too, evidently, except that there were remnants of us left here and there, for instance in a few coastal regions, probably living off shellfish and such till normal life returned, the survivors could resume food gathering as usual, and people began again to populate the planet with what would become the ancestors of us all. Estimates are that at our lowest point in that crisis only about 1000 adult humans were alive. Some scientists think as few as 40 child-bearing women remained to continue our kind and so eventually dominate the orb with seven-plus billion of us. How might things be different without our kind? Here are a few of the ways, according to what can easily be discovered through library and web reading:

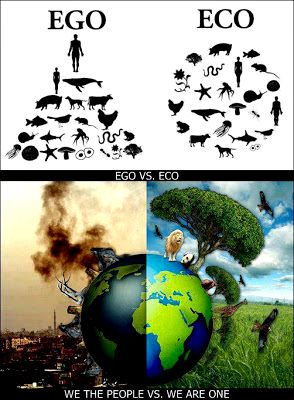

Trees - The number of trees left in North American today is reduced by probably 95-99 percent from what would have been the case if not for the presence of people, our development, and a multitude of agricultural and ranching projects. Also, there is now almost no old growth forest remaining, whereas without us most trees would fit that category. Besides Pacific Coast giant redwoods and sequoia forests, there would be vast expanses of old growth hardwoods and softwoods, with deciduous and coniferous trees in abundance and stretching both coast to coast and from well inside what is now Canada through present day northern Mexico. In the area we now regard as New England, for instance, there were once oaks and sycamores 10-20 feet thick and white pines 250 feet in height. Imagine virgin, old growth forest in most areas, starting from a short distance inland from the sea, their expanses mostly broken but by river valleys, deserts, grasslands, and mountains. Lightning would certainly have sparked fires in temporarily dry areas, and occasionally these would grow long and hot enough to consume old growth, from which patches of younger trees would compete with one another for the new space and light at forest floor and ground level, but for the most part the burning would just take out smaller brush or already dead or fallen wood, adding natural fertilizer to the mix. Animals - Our hypothetical viewer of an area free from human intervention would likely be struck at once by the sheer profusion and variety of wildlife. Among mammals alone, besides millions of bison, there would have been a multitude of deer, coyotes, bats, goats, elk, pronghorns, moose, foxes, mink, badgers, wolves, porcupines, mountain lions, skunks, and peccaries. There might also still be many of the now extinct mega fauna, including ground sloths, saber tooth tigers, mastodons, giant beavers and armadillos, short-face bears, mammoths, camels (actually more closely related to llamas), horses, American cheetahs, etc. There would as well be innumerable wild birds, some of which we would recognize and others totally foreign to us, not to mention great quantities of common and exotic amphibian, reptile, and fish species. Mushrooms, spiders, insects, crustaceans, and mollusks would likely be so numerous and diverse as to keep my science-nerd spouse delightedly busy for several lifetimes. Beaver ponds - Most untrammeled rivers and streams would be marked by a spacing of countless beaver dams, creating luxurious meadow systems through much of our North American continent. These in turn would assure perfect habitat for many creatures and for flora needing abundant light, rich soil, and water resources. Before trappers took out the majority of beavers for pelts, this was the norm in many areas throughout the region. The beaver ponds in turn would also have prevented most flooding and yet spread vital water and silt through wide areas in a stable manner, easy for life to profit from. Topsoil - Without over grazing and farming or paving over practices or simplistic engineering projects, most areas of North America probably would have several more feet or even yards of rich topsoil. Not only does this preserve healthy root systems but it helps allow for the soaking in of rainfall and its slow provision to plants and animals between showers and seasons. By contrast, for instance, Texas hill country, known for its rocky outcroppings and flash floods, now has little average thickness of topsoil left. Coastal areas - The conditions in early New England may illustrate how things might be with few or no people about. When Native Americans belatedly showed up on the cold shores of a state we now call Maine, they encountered huge stores of cod, many so big they could be caught by hand, plus vast quantities of herring, clams, oysters, crabs, lobsters, and millions of water fowl, their eggs plentifully available. Grasslands - Many areas of our continent are perfect for savannas or grassland. They are naturally augmented by lightning strike fires, these consuming dead vegetable matter and at the same time fertilizing the area for the good of subsequent plant growth. Thick mats of grasses' roots and decaying matter hold often scarce moisture, prevent erosion, and offer subterranean hostels for certain animals. The streams are typically full of fish, crustaceans, and water dwelling insects or mollusks. Without the intervention of people, creatures adapted to the savannah would live in abundance in these environments, including prairie chickens, bison, prairie dogs, bobcats, bald eagles, mountain plovers, greater sage grouse, ground squirrels, prairie kingsnakes, wolves, coyotes, foxes, black-footed ferrets, badgers, gophers, and pronghorn. Thinking about a world without humans is only an interesting idea in itself. To me, there is a lesson in it, though: when one species comes to so dominate the biosphere that the results taken together are supremely adverse to much of the rest of the environment, nature tends to apply corrective measures if that life form does not on its own adapt in a more sustainable way. Conservation measures have a vital place in our priorities. So do finding ways to live responsibly with our floral and faunal friends. Certainly we can instead ignore the needs of the balance of the natural world and re-create the surface of Earth in a manner to make it fit only for ourselves, thus permitting, perhaps, the addition of yet a few billion more humans. Is this, though, truly the best use of our kind's supposedly superior intelligence? A little wonder at the awesome spectacle of bountiful life as yet all around us may give answer. Let us not forget the needs too of Brother Bear or Sister Honeysuckle as we plan for a better present and future for ourselves and our pearly world. Primary sources: -How Human Beings Almost Vanished from Earth in 70,000 BC. Robert Krulwich in www.npr.org; October 22, 2012; -The World Without Us. Alan Weisman, Thomas Dunne Books, St. Marin's Press, New York; copyright 2007. |