by Larry

October, 2009Lessons from the Carrington Super-Flare Event

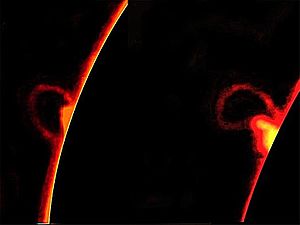

Solar flares of the intensity of this Carrington Solar Flare are now not expected to occur more than about once per half-millennium, which is just as well for the health and stability of modern civilization. Scientists caution, however, that solar flare research is still in its early phase and that we do not yet know enough to rule out a repeat of an 1859 type event in our lifetimes. The 1859 super-flare caused devastation for the communication systems of even that day, with widespread melting of telegraph wires in Europe and North America, igniting numerous fires. Much upper atmosphere ozone was destroyed by the event as well. Northern lights phenomena, normally visible only in higher latitudes, were noticed as far south as Cuba, Rome, and Hawaii. Those in the Rocky Mountains were so bright that during the middle of the night gold miners there got up and began preparing breakfast, convinced it must be morning. In 1989, a powerful solar flare knocked out communications throughout much of the French speaking Canadian province of Quebec. But the Carrington flare was three times stronger than that one. A similar occurrence today would likely overload power and communications lines with electrical surges and turn satellites into useless hulks of metal. As much of global commerce depends on the rapid transmission of information and communications via satellites and electrical grids, the 2008 near economic meltdown might seem afterward a mere hiccup compared with the havoc such a super solar storm could create. A few examples: controllers might be without data with which to guide landing aircraft in the congested skies above major airports; ATMs may stop working and providing cash; long-distance telecommunications could cease; credit cards authorizations may no longer be made; etc. To begin to restore things to normal might take many months. Meanwhile, depletion of upper atmosphere ozone would allow more of the Sun's powerful rays to reach the Earth's surface, detrimental to the biosphere generally and increasing the incidence of skin cancers. With current technology, there is little that might be done to protect vulnerable grids and satellites from a Carrington-class solar event. At best, operators would have a chance to save information and shut down vital earth-based systems in advance of a super-flare's arrival, to minimize losses and accidents. Satellites in orbit might simply have to be replaced. It would be best to have a series of new ones waiting in the wings for launch once the solar storm had passed. Given the stakes and the importance of preventative actions in advance of a new super flare's appearance, the study of solar flares and monitoring of the Sun's surface are given elevated priority among space agencies worldwide. Primary Sources: A Super Solar Flare. Trudy E. Bell & Dr. Tony Phillips in Science@NASA; May 6, 2008. 150 Years Ago - The Worst Solar Storm Ever. Robert Roy Britt in SPACE.com; September 2, 2009. |