by Larry

January, 2013Counting on the Countdown Till a Nuclear Fuse IgnitesWhen I was a child, peaceful applications were just being found for the creation of nuclear fission energy. Soon thereafter, cities and large naval vessels were being powered respectively by stationary or mobile nuclear plants. Until Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and the recent earthquake and tsunami destruction of Japanese nuclear plants, with significant release of air- and water-borne radiation, fission technology nuclear plants were thought by many to be the best answer to a need for ever more and cheaper energy for a large and advancing world population. Now that optimism is tempered. Yet as I was growing up we were told that, awesome as nuclear fission was, "just around the corner," or later, "by the end of the 20th Century," we would through nuclear fusion have unlimited energy and at a fraction of the cost of modern power sources. What is nuclear fusion? In layman's terms (all I would understand), it is the creation of new atoms by means identical to what the Sun does continuously as it turns hydrogen to helium, thereby releasing huge amounts of energy, enough to blaze brightly and hotly through the Solar System for billions of years. Scientists have told us that in just the next few decades we could master the engineering to create tiny suns and controlled fusion reactions here on Earth, after which energy would become so cheap we could give up the fossil fuel fix that threatens to raise the temperature of our planet beyond what most of us would find tolerable. Humanity actually accomplished nuclear fusion back in the early 1950s. The result was the hydrogen bomb. Unfortunately, it did not represent the kind of control needed for successful non-destructive fusion uses.

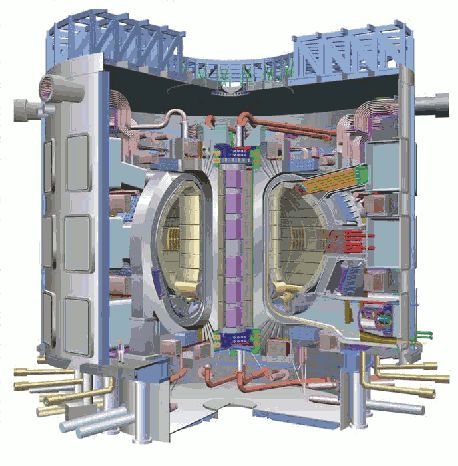

One effort, for instance, is being carried out at The National Ignition Facility (NIF) in Livermore, CA. The idea was to use lasers to create more pressure and higher temperatures than in the Sun's center, which, it was believed, would smash atoms together and create for the briefest of instants a diminutive sun as a moment of controlled nuclear fusion occurs, a process referred to as "ignition," the successful creation under laboratory conditions of more energy output than the input required. So far, however, after several years and billions of dollars spent, we do not have ignition. People evidently are not sure why not. Were the workers at NIF, or at ITER (formerly the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor), another tremendously expensive but so far disappointing nuclear fusion endeavor, successful, their small-scale triumphs might be ratcheted up to large scale nuclear power plants unlike any seen before. These would run on water, their more or less endless source of hydrogen, would create no radioactive waste, and might put out ten times or more the energy required for their operation. This would certainly be a result worth all the hopes, funds, and time put into achieving ignition to date. However, as each new target for ignition passes without the needed effect, a realistic assessment is now appropriate. Can this countdown to a "nuclear fuse" ignition be counted on enough for the expenditure of vast new sums? And can it achieve its goal in time, before atmospheric greenhouse gases build up enough to cause great havoc? Already we are told in the news that recent global hurricane activity averages twice the power seen several decades ago. And in many places "100-year" droughts and floods are now occurring with more like one in ten odds for any given year. Global warming may have proceeded too far for our species to do much to stop it if another generation passes without substantial fossil fuel use abatement. Like a vast ocean liner, the global system of balances, currents, and feedback loops within the ocean and atmosphere, and even among living things in the biosphere, takes a great deal of energy to be set on a new course, but once it is proceeding on that course, as apparently is occurring with global warming, its progress on that new route is to an extent inexorable. Per In Livermore, Still Waiting on Nuclear Fusion by Amy Standen in Quest, October 27, 2012, Christopher Paine of the Natural Resources Defense Council recently said "Dealing with climate change is a 20-30 year planetary emergency. Fusion energy is irrelevant in that timeframe. Humanity needs to change its ways now. It needed to change its ways yesterday. Fusion energy is a 50 to 100 year project with no assurance of success." Yet I remember that in the 1960s Paul Erlich in The Population Bomb was predicting mass starvation of billions of us long before now, simply because there could not be enough for us all to eat. Then, a few years after his dire predictions, new agricultural techniques, collectively called "The Green Revolution," seem to have changed all that, and our numbers just keep rising. Only a couple generations ago it would probably have been unimaginable how vast the transformations that have occurred as a result of the internet, computers, laptops, I-pads, smart phones, social networking, and all the other large and small applications of a pervasive digital revolution. Ours is an innovative type of animal, and among all our seven plus billions there must be more with the genius of a Bill Gates or a Steve Jobs. If but one of them comes up with a handy "Mission Impossible" solution to how to get nuclear fusion ignition to work or how otherwise to curtail global warming in short order without serious side-effects, we may have a far brighter celebration of the next century than seems possible with a currently more limited view. |