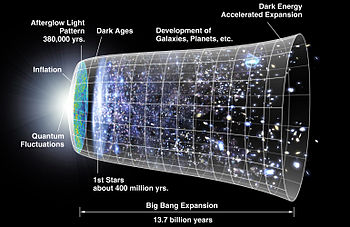

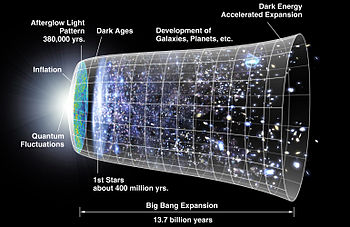

Big Bang Illustration (Wikipedia)

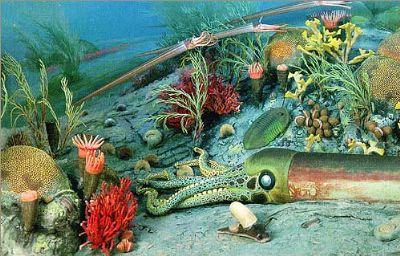

On the brighter side, insignificant in duration as we may feel compared with the longest living things, we probably in this modern period can get to be several times as old as our prehistoric ancestors. And consider the poor octopus. Though relatively intelligent, it will never develop an undersea civilization, for the simple reason that it and all its memories die only about a year after hatching.

For this issue, I thought I would simply reflect and free associate a bit on what time means to me. The topic felt more poignant and personal after I heard two statistics recently. First, people supposedly lose 1.8 years of life expectancy for each year they retire earlier than the traditional age of around 65-66. Since I retired at age 58, the math indicates I should be dead by now. Second, I have just heard that the average age of widowhood in this country is 56. Even apart from the just preceding poor prognosis for my increased longevity, since Valerie, my wife, is now over 55, the odds evidently support my demise within the next several months. I am philosophical about all this. On the other hand, these are just two more indicators that we ought not be complacent about how much more time we have.

Big Bang Illustration (Wikipedia) |

Even now, in what we consider the present, things can be seen by one observer that appear to have happened in the past while to another, not all that distant but at a different angle relative to that which is being viewed, it may be going on at more or less the same time or even have not quite happened yet.

I understand time may be seen as in one sense relative and in another as omnipresent. Perhaps there is no time, but only a temporal outlook or consciousness. Maybe time is like a frozen river, which seems in part to be nearer its beginning (the past), in another part closer to its middle (the present), and finally in part closer to its end (the future), at least relative to an observer somewhere along its course, yet which actually is just always and at once present along the whole of its length, it being the observer who "moves" in relation to it.

We think and live, though, for the most part linearly and appreciate or even notice just one instant (if any) of the full expression of time at a time, this very split second. If we miss that, we lose a lot. Assuming time is precious, it may be especially so when we often are distracted by imaginings about the past or future and fail to participate in what is going on right under our proverbial noses, here and now.

Yet, even the chronologically sequential and forward moving quality of time may not be an absolute. As in the Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, in which the protagonist, Billy Pilgrim, lives now here, now there in time, even experiencing his death before a number of other disordered events of his existence, psychological time can vary from "real" time's apparent norm. People with mental and/or brain disorders may find themselves stuck in a prior time or able to remember things from a distant past as if they are occurring currently while missing much of present happenings. Others have no sense of past, their long-term memories obliterated, so that every few seconds they witness life more or less completely afresh. In dreams our time settings seem to leap about whimsically. And everyday consciousness flits from one epoch in our lives to another or with unruly abandon projects us ahead. Meditation can show us that such diversions from the present focus occur even more typically than awareness of the stodgy steady march of time as measured by our clocks.

Prehistoric Life (Wikipedia) |

Physicists tell us there are time- and space-intensive "regions" (such as ours) and also "places" in which neither time nor space exist, where these concepts have no meaning at all. Before the hypothetical big bang from which our universe is said to have sprung, there was, they tell us, nothing to which we could relate as having length, breadth, height, or temporal extension. Of course, we could not have lived there anyway, so maybe it is academic!

Similarly, we are told that within black holes, which may occur both throughout existence (in extremely tiny form and for less than an instant each), and, much more vastly, in the centers of galaxies, including our Milky Way, things get so disorganized that time and space themselves are no longer possible. It is as hard for me to grasp what reality must be like "there" and "then" as it is to fathom the consciousness of extremely smart aliens, perhaps ones who have been more or less technologically advanced not merely for a few hundred years, like our kind, but for tens of millions of years and who might view us more the way we do octopi.

On social media sites now, one can in a few moments glance at representations of the timelines of any of hundreds of millions of people. Our stories, seemingly so diverse, may actually be remarkably similar. As in the Thornton Wilder play, "Our Town," we each are born, grow up, and live out our lives as best we can. Soon enough, like that script's Emily, we die. As the play's minister says of marriages, so perhaps with our lives: "one in a thousand is interesting." Yet being interesting is not what it is all about.

There may be a spiritual role we have to play in this realm of being, or not, but in the living, loving, pain, hope, curiosity, sadness, mystery, laughter, awareness, and loss that are the truth about our time here now, there is much cause for awe. As in the Flower Drum Song, "A hundred million miracles are happening everyday!" Oddly enough, our millions of new daily moments may be among them.

Even if particularly challenging on occasion, perhaps it is best if we really enjoy our time here. As G. I. Gurdjiev and P. D. Ouspensky might have noted, for each of us and however long it lasts, it is extraordinary!