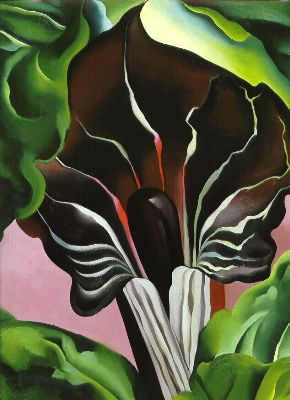

Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. II, 1930 - National Gallery of Art

Georgia O'Keeffe

Georgia O'Keeffe's life, 1887-1986, spanned nearly a century, plenty of time for her to make a major mark on the art world through her painting, pottery, and writing. The extent of her contribution is the more remarkable since as her career began women were little esteemed professionally. Yet, beginning in her later decades she has been recognized as one of America's leading artistic lights.

Jack-in-the-Pulpit No. II, 1930 - National Gallery of Art |

In her childhood, O'Keeffe lived on a Wisconsin farm, where agrarian prairie landscape features and crop or flower forms were set against a dramatic bowl of sky. While she was in her teens, the family moved to Williamsburg, VA. Her initial reactions to the stifling rules and roles for young white women in that area appear to have set the tone for a certain independence, even rebelliousness, she exhibited in the balance of her life.

Subsequently, she was a student of art or teaching it in Chicago, IL, NYC, Lake George, NY, Charlottesville, VA, Columbia, SC, Amarillo, TX, and Canyon, TX. But she would come into her own as a painter with a mature and unique style after relocating to NM, where the stark, empty, yet colorful geography again is set off by a heavenward grandeur. Here she would spend much of her time during the lengthy middle and final portions of her career.

One of O'Keeffe's gifts was to see things clearly, which may, however, not be just as others viewed them. Trained in the tradition of artistic realism common in the 19th and quite early 20th Centuries, she at first sought to portray still life, people, or landscapes as they were conventionally viewed. But before long she felt frustrated by what she regarded as an uncreative, stodgy process and actually gave up on art for several years. Later, however, she came under the influence of Alon Bement who taught the then radical ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow.

Though Dow was himself scarcely brave as either a man or painter, his notions of art were quite adventuresome and innovative within the realms of occidental talent and borrowed in turn from the works of Japanese masters. In contrast to the US art of the time, which was merely duplicative of classical works, Dow suggested a portrayal that holistically encompassed at once the painter's artistic expression, insightful awareness of the subject in context, and a fitting or balanced arrangement of the visual elements.

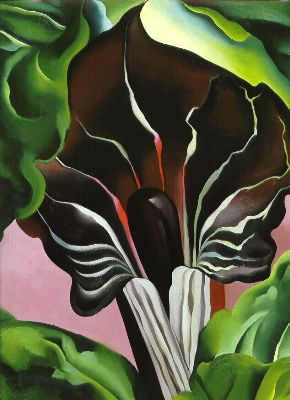

Red Hills & Pedernal, 1936 - Museum of Fine Arts, Museum of New Mexico |

Dow's approach would permit, inspire, and indeed demand that the painter put the artist back into his or her art. His notions encouraged students to be in a sense poets, not merely in their painting but through their entire lives. True art could not be divorced from the living out of a poetic vision.

Seeing and feeling the validity of this approach, and emboldened herself more than her artistic and intellectual male mentors, O'Keeffe combined an inner emotional insight, compelling authenticity, and aesthetic composition in the painting of flowers, their features lavishly swollen onto large canvases or paperboards, where the beauty of the images, too often ignored when tiny, could be appreciated in all their intensity and even, some said, in their overwhelming, yet gentle voluptuousness.

Additional influences on O'Keeffe were William Merritt Chase and Frank Dumond.

In 1924, O'Keeffe would marry another key artist of the time, Alfred Stieglitz, also one of the period's iconoclasts, but found his concepts of art too aggressive for her sensibilities and so did not follow his example in her painting. Ultimately, his work would be dwarfed by her own in scope and power. Yet her growing renown (or notoriety) was partly due to many photographs, including nudes, he took and published of her. And it was he who had first exhibited her early works, in NYC, back in 1916. As both of them were of a somewhat contentious temperament, however, it should not surprise that their matrimony involved less than perfect bliss. O'Keefe, for one, though she may have expressed great passion in her paintings, wanted little to do with it in the bedroom.

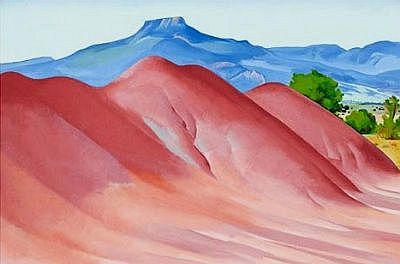

From the Faraway, Nearby, 1938 - Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection |

In 1930, following a nervous breakdown, O'Keeffe was offered a friend's place for a summer stay in Taos. Her sojourn there was restorative, and she began frequent visits to NM. These continued until the death of her older husband, in 1946, after which she moved there permanently, at a time when the largest roads were still unpaved and the area as yet lacked indoor utilities. O'Keefe was thus a real pioneer in more than one sense.

Southwestern motif pictures came to dominate her later efforts. In NM she also tended to paint more naturalistically, less schematically and romantically. This was to a degree, O'Keeffe said, because she objected to the interpretations critics had made of her paintings in the former, more lush styles. Nonetheless, the new works often retained a sense of excitement, even conveying wild or exotic themes. At times her images seemed so crackling with energy that a tornado or bolt of lightning might strike at any moment. Her images had the freshness one might expect from an artist seeing things for the very first time. This gave them at times a luminosity, or at others an almost drug-induced vividness, as though she was, through the paintings, trying to convey her ecstasy at the beauty glimpsed in shells, bits of flora, sky vistas, trees, skulls, isolated adobe structures, or the kaleidoscope of scenery.

In 1976 she received the Medal of Freedom for her life's work. In 1985, she was given the Medal of the Arts. Georgia O'Keeffe is regarded as the first major American female artist and, regardless of gender, among the very best creative talents our country has produced.