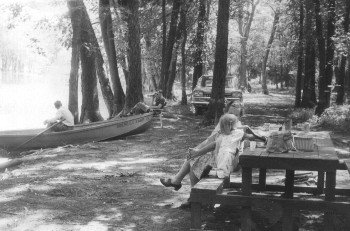

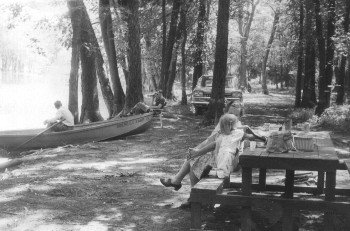

Idyllic day by the Kankakee River, June, 1960

Valerie at table with Mary (Val's maternal grandmother),

Chuck (maternal grandfather) in boat, John (father) in chair.

Idyllic day by the Kankakee River, June, 1960 Valerie at table with Mary (Val's maternal grandmother), Chuck (maternal grandfather) in boat, John (father) in chair. |

This was not just any net, either. It was a special net that we used often when I was growing up. Unlike a simple dip net that had a handle and a loop with mesh, this one had two four-foot poles. Attached between them was a six-foot wide heavy duty mesh, with lead sinkers tied on to the bottom side. It took two people to wield this massive seine so using it was always a cooperative affair. This net was made for rivers and the technique was simple: each person held one pole firmly anchored to the bottom of a rocky waterway, with the net stretched out between. Then they both moved the upstream rocks around with their feet to dislodge any creatures hiding underneath. It was even better if we had a third person to "dance" around in the current above the net, an especially enjoyable pastime in the heat of summer. In the fast, muddy water of the rivers we frequented, we never knew what was washing into our trap until we scooped the net upwards and carried it to shore to examine the contents.

Depending on what we were trying to catch, we would save some of the creatures, then dump the rest back into the water. Sometimes we'd be after bait for fishing. Then we'd separate out the soft-shelled crayfish and peelers (crayfish about to shed), the really big crayfish for tails, the leeches, and the hellgrammites. Other times we were just after crayfish to feed our ravenous pet turtles. They ate so many that we would catch five pounds or more at a time, then freeze most so we would have a constant supply ready for them. We even stocked our aquariums with tiny fish caught in this manner.

The most important function of the net, though, was as entertainment. My sister and I could stay busy for hours catching and looking at the things we found. The fauna in the rivers was as alien as if it came from an unseen planet. We could see the surface of the water, but nothing of the myriad creatures dwelling below. Picking up rocks to look at the tiny invertebrates that clung to them satisfied part of our curiosity, but we knew there were many more animals swimming about that fled our prying activities. With our simple tool, we could pull up a sample of their world and examine it in our restricted dry land environment.

We were very thorough in our exploration of the river habitats we could access. We'd move big rocks, wade in as deep as we could, and even brave the vegetation along the shoreline to flush out new creatures. Once we'd felt we had a decent haul, the technique was to lift the net quickly and wade over to the shore before the tiniest creatures wiggled through the mesh. Once laid out on the ground, picking through the weeds, sticks, debris, and occasional rock would yield any manner of small beasts. We commonly caught crayfish, leeches and small fish. The fish could be anything from common minnows to baby bass, gar, carp, and suckers. Small bottom dwelling fish like madtoms, darters and stonerollers often made an appearance. The more delicate animals were quickly thrown back into the water before they dried out. Insects and their larvae were the most varied creatures. From the giant hellgrammites to stonefly, mayfly, dragonfly, and water beetle larvae, we became experts at identifying these usually unseen denizens of the river bottom. Some of the insects were common, like diving beetles, but we also found the more exotic ones, like water scorpions and caddisfly larvae. If we were exceptionally lucky, we'd bring up a baby turtle, tadpoles or frogs. Then there were the spiders. Because we went through vegetation, sometimes large fishing spiders would end up in the net. This was cause for much squealing and frantic flailing.

Since other people used the well-trodden path along the river, sometimes a passerby would stop to see what we were catching. They would often be surprised by all the different things that lived in the water, as we pointed out the various species. It might be comparable to birdwatchers helping people appreciate the previously unnoticed residents in the trees overhead.

With the help of the net, our experiences at the river involved more than just sitting on the edge and wondering what animals resided unseen within its depths. We had actually made their acquaintance.